Net zero homes are a pipedream without the right incentives and regulatory co-ordination

The Skidmore review is vast in scope, covering everything from agriculture to transport, manufacturing to waste, tax policy to skills … and yet, there are some specific recommendations at the back of the paper which could have a big impact on Mixergy and the wider move towards net zero homes. The idea of rewarding demand flexibility whilst moving to a half-hourly settlement for the whole electricity market is particularly exciting (and indeed critical) given the emphasis on expanding offshore wind whilst targeting 70GW of solar power by 2035.

When I started Mixergy with my co-founder and friend Ren Kang, our vision was to help decarbonise homes and the grid through the humble hot water tank. The idea was to achieve this by re-engineering hot water tanks so that they would behave more like smart batteries, operating with greater efficiency whilst responding to flexible tariffs and grid frequency to facilitate more renewable generation.

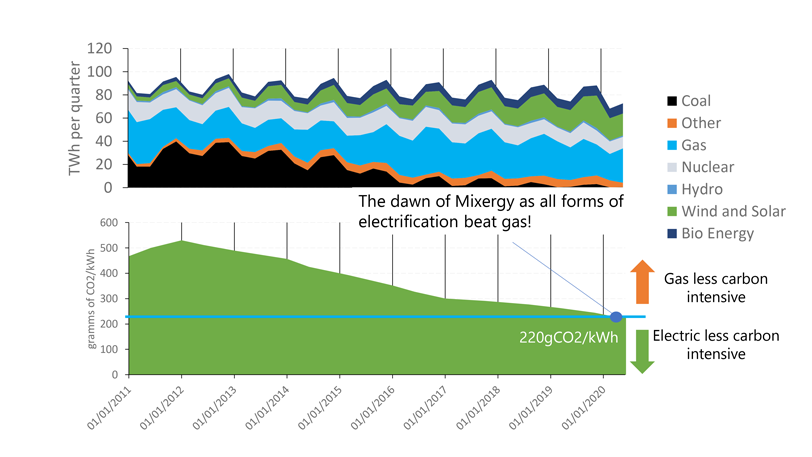

We started this mission in 2014 and at that time, the carbon intensity associated with electric heating was more than double that of gas (~450gCO2/kWh against ~220gCO2/kWh, factoring the relative efficiency of electric hot water tanks and gas boilers). Since then, generation across our grid has undergone a seismic transformation. The carbon intensity of electricity now plummets below gas on a regular basis (in fact whenever the wind blows).

In the last week of 2022, the carbon intensity averaged 73gCO2/kWh, less than half that of gas! Over the same timeframe, Mixergy has installed thousands of smart hot water tanks which can now switch between gas or electric heating depending on the price or carbon intensity of electricity at any moment in time.

The heart of the Skidmore review is about moving away from fossil fuels and for us, this ability to switch is a key stepping stone towards that. The following graph shows how the UK’s generation mix has changed along with grid carbon intensity since 2014:

As we can see, a great deal has been achieved when it comes to decarbonising the grid. Alas, the technology underpinning our domestic heating systems has been far slower to adapt meaning households are missing out on the cost and carbon savings that should be available from the offshore wind and solar PV already installed. This is made worse by the marginal pricing model of our energy system forcing us to bear the cost of gas-powered generators!

Why is this?

There are many reasons, clearly, energy companies can respond quickly to sudden shifts in incentives occurring in markets and across regulation. People’s homes, on the other hand, are difficult and sensitive spaces to change so suddenly. But a key factor is the regulation across our built environment, which is often slow, uncoordinated, and struggles to relate to real-world incentives.

At Mixergy, we are positive these problems can be addressed. We know that the likes of BEIS, BRE, OFGEM, and National Grid are driven, well-intentioned and capable. But these bodies aren’t always joined up and are too often making decisions in isolation of each other. This creates barriers for businesses like ours, slowing our quest to get UK homes to net zero.

I took part in the Skidmore review. Below are the reflections we shared on the challenges we’ve faced over the years, with recommendations on how to combat them. Strap yourself in!

1. Glacially slow regulation

For any start-up or small business, resources are limited and time is of the essence. At Mixergy, it has taken considerable investment and time to get regulatory endorsement through the Building Research Establishment (BRE), who determine the requirements for new build energy standards alongside Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) in the retrofit market. This is for a good reason; BRE has a delicate balance to strike between allowing new technologies into the built environment without letting a wild-west situation emerge. It takes time to validate technologies and BRE themselves are limited in bandwidth.

However, this creates a ‘chicken and egg’ problem. Often, data from multi-year trials is needed for the recognition of a new technology in the ‘Standard Assessment Protocol’ (SAP), this process from the BRE attribute points to building designs across carbon intensity, energy consumption, and cost. A new building has to pass a SAP threshold to be allowed planning permission.

But new build and social housing developers (who can rapidly test new products) are hampered by the need to comply with the existing version of SAP in the first place. So, technology needs to be validated in order to be regulated, but large-scale pilots to validate new technology can’t be trialed without regulatory endorsement first.

‘Sandpit projects’, where new technologies are granted temporary regulatory relief within large-scale pilots, could solve this problem, speed up the process of tech validation, and reduce commercial risk and time to market.

2. A lack of co-ordination between regulation and policy around net zero

Energy labelling is a striking example of this. Today, energy labels promote gas combi-boilers as ‘A rated’ whilst punishing direct electric storage systems which can never exceed a ‘C’ rating. This is in spite of the lower carbon intensity of the grid and the higher efficiency of modern hot water tanks. Advances in modern insulation materials means that standing losses from hot water tanks are small compared to the cycling losses of a modern combi boiler.

To make matters worse, energy labelling is completely decoupled from SAP which means consumers are told one thing which is completely at odds with regulation for new build developers. At the same time, new build regulations within SAP discourage technologies which could facilitate Demand Side Response (DSR) at scale, the process of turning things off when the cost/carbon of energy is high and on otherwise.

Why is this a problem?

To take just one example, developers now routinely specify solar PV on roofs to obtain regulatory approval for new homes. Great right? Well, when it comes to commissioning these systems, the same developers are often told to curtail the output of the solar array by the local DNO who is worried that nearby power cables or transformers might be overwhelmed. This is in spite of the fact that home battery and hot water storage technologies, combined with DSR, could allow much more PV production without overloading the local power network.

Curtailing PV means limiting the potential cost and carbon savings for households who both generate and consume their own electricity, otherwise known as prosumers. We know that encouraging DSR and storage technologies would allow us to increase PV on a street by up to 50% in a new build development before voltage problems are encountered.

Stepping back and looking across the full gamut of DSR services, we need to figure out how to reconcile the needs of the DNOs concerned with local cables in a distribution network against the National Grid’s need to maintain frequency stability at a national level, and alongside the commercial needs of utilities operating on the balancing market.

Conflicts between these elements of the system becomes more likely as we move further from the traditional centralised model of power generation, transmission, and distribution towards decentralised prosumers with roof-top PV, EV chargers, and heat pumps. Resolving these conflicts can be achieved with a bit of joined-up thinking between BRE, local DNOs, and the National Grid.

3. Lack of transparency and accountability across regulatory bodies

This happens across a number of fronts:

Energy labelling: At Mixergy, we challenge the often unhelpful incentives created by product energy labels (discussed above). In 2019, Ren and I published a paper in the Journal Energy on this subject and submitted it to the European Commission. We suggested some relatively simple corrections to the calculations within the directive to avoid penalising electricity in favour of gas. But the commission has yet to review it. We believe post-Brexit, the UK is now simply following the European labelling scheme without the bandwidth or inclination to adapt for our own generation mix or policy objectives. As such, there isn’t a clear and transparent process to understand the decisions behind energy labelling.

Tax incentives: Another area which could be improved with greater communication is the application of VAT exemptions for energy-saving products. Although Mixergy has received endorsement from BRE and the Energy Savings Trust, it’s proving difficult to capitalise on the VAT relief often used by other energy-saving products (such as central heating controls).

Implementation of SAP: In June 2022, it was suddenly announced by Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC), that new technologies would be suspended from the new build regulatory regime due to technical difficulties in its implementation. This decision came as a bit of a shock to the cleantech sector as a whole and created setbacks in the commercial pipeline for many whilst tilting the playing field in favour of incumbent fossil-fuelled technologies.

Greater transparency across our regulatory environment would help avoid bad regulation and perverse incentives whilst creating a more level playing field for cleantech businesses working to decarbonise the UK’s housing stock.

4. A failure to leverage incentives

New build and social housing developers should be rewarded and not punished for going beyond minimum standards. We have the technology to validate the energy performance of homes at low cost through smart meters, and sensors are now routinely embedded within modern heating control systems. This space is ripe for creative thinking around incentives! For instance, linking corporate tax levels to real-world energy consumption and carbon performance could be transformative. We could mobilise an army of engineers and SAP assessors towards the delivery of net zero rather than simply gaming regulations to achieve the lowest cost of compliance.

Incentives could also be improved for landlords (social or private) and homeowners through green mortgages, stamp duty, and/or EPC thresholds for the rental market, along with levels of tax relief on rental income being linked to real world energy performance.

Finally, we are in a strange situation where the cost to decarbonise our energy system is applied to electricity through green levies. Over time, these levies need to be shifted from electricity to gas, particularly as energy prices begin to stabilise and perhaps fall in future. This would help close the spark gap between gas and electric heating solutions to the point where electric heating becomes a no-brainer for private homeowners (the largest, most difficult-to-address segment in the market). This could not be done without consideration for those in fuel poverty who rely on gas at present and do not have the means to upgrade their homes or heating systems.

This wish-list is by no means exhaustive and yet already feels daunting! However, as the Skidmore review has shown, many are working hard to addressing them. We hope they are inspired by what has been achieved by the UK’s power sector, who have brought the carbon intensity of electricity below gas within 10 years. If we can solve some of the regulatory challenges around the built environment, we can accelerate the transition to electric heating in our homes and who knows, perhaps net-zero by 2050 won’t seem such a distant goal after all…